If your systems can’t tell what counts as personal data, they can’t protect it.

The Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act requires businesses to process personal data responsibly — but leaves it up to you to figure out what “personal data” actually is in your business context. This creates a serious operational challenge — especially for Banking, Financial Services and Insurance (BFSI) companies handling vast volumes of customer data across multiple systems.

Misclassifying data — or failing to recognize personal data flows — can lead to missed consent requirements, inadequate security controls, regulatory penalties running into crores, and lasting reputational damage.

In this article, we break down how to identify personal data in your systems — by the end, you'll have a clear, actionable understanding of how to approach personal data classification in your organization.

Understanding Personal Data: Not Always Straightforward

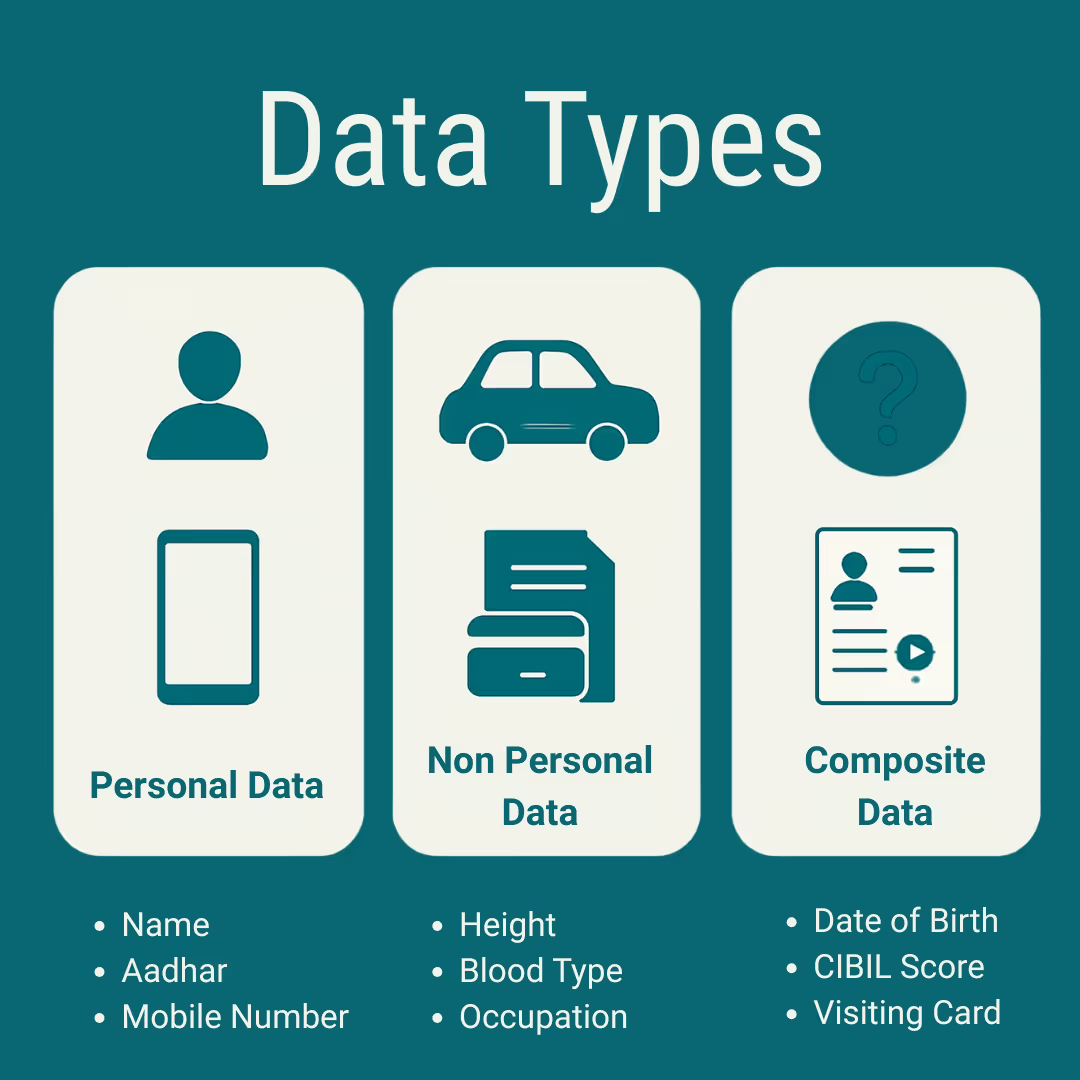

The DPDP law applies to “Digital Personal Data”. Personal data means any data about an individual who can be identified using that data. If collected digitally or is digitised after physical collection, it will count as digital personal data.

Some data points are clearly personal:

- Name

- Phone number

- Aadhaar or PAN

- Account number

- C-KYC number

- Photograph

- Biometrics

However, ambiguity arises with composite data—information that becomes personal only when combined with other details:

- Loan application forms combining occupation, income, city, and partial address.

- Insurance claim forms linking policy numbers with mobile numbers.

- Branch visit logs combining time of visit, phone numbers, and service requested.

- KYC documents partially masked but retraceable with transaction records.

Even if these data points seem harmless individually, when combined, they identify individuals and may fall under the DPDP framework.

For BFSIs, even a customer ID, branch account number, or policy number — while institution-specific — may become personal if linked to identity. Similarly, location coordinates during a transaction (e.g., branch geo-fencing data) could qualify as personal data.

Example: A vehicle registration number might not identify someone on its own. But if your system stores it alongside loan application details, it becomes traceable to an individual, thus qualifying as personal data.

As things stand, the DPDP Act does not provide a detailed checklist or a clear enough definition of what qualifies as personal data — leaving businesses to make these determinations themselves. The recently released Draft DPDP Rules also do not offer additional clarity on this front, further emphasizing the need for a cautious and conservative approach to classification.

Purpose Determines Classification

Under the DPDP Act, personal data is defined by identifiability—not just the content of the data, but whether the purpose of processing it involves identifying someone.

Instead of merely asking, "Is this data personal?" consider: "Am I using this data to identify or profile someone?"

If the answer is yes, then it should be treated as personal data and protected accordingly.

Why Misclassification is a High-Risk Mistake

Getting personal data classification wrong can have serious operational, legal, and reputational consequences under the DPDP Act.

Here’s how misidentifying personal data can play out:

- Missed Consent Collection

If you fail to recognize that a piece of data is personal, you may not seek valid consent or establish another legal basis for processing it. - Improper Security Controls

If you under-classify sensitive data as "non-sensitive," you may apply lighter security (like basic masking) instead of encryption or vault storage — making breaches far riskier. - Regulatory Non-Compliance

In case of an audit or a data breach, regulators may determine that you failed to meet DPDP obligations for lawful processing, data minimization, purpose limitation, and security safeguards. - Fines and Reputational Damage

Under the DPDP Act, penalties can be significant — running into crores of rupees depending on the severity of the violation. Publicized non-compliance, especially in the BFSI sector, can erode customer trust overnight.

.avif)

Imagine ICICI Bank collects partial vehicle registration numbers as part of a loan application. The team assumes that since the number is partial, it’s not personal data.

As a result, no consent is collected, and no lawful processing basis is documented.

Later, the bank starts using this registration data to cross-sell motor insurance products to the same customers — sending targeted communications based on the vehicle information collected during the loan process.

During an audit, it is found that:

- The purpose (loan processing) involved identifying individuals.

- The registration numbers, combined with customer profiles, clearly qualified as personal data.

- Since no consent was collected for either the original collection or the subsequent insurance marketing use, the bank had no valid processing basis under the DPDP Act.

Result:

ICICI Bank faces regulatory scrutiny for unlawful processing of personal data, is forced to cease certain cross-selling activities, must issue compliance remediation reports — and risks losing customer trust due to unauthorized use of personal information.

Other Scenarios Where Classification Matters

The ICICI Bank example is just one illustration of how easily classification errors can creep into day-to-day operations — even in highly regulated sectors like BFSI.

In reality, misclassification risks exist across a wide range of typical business workflows. Here are a few more situations where failing to correctly identify personal data can create compliance gaps:

Loan Processing

Your system captures a customer's name, PAN, occupation, vehicle data, and location to generate a credit profile.

While some of these aren't personal in isolation, together they can clearly identify someone — making the entire dataset personal and subject to DPDP compliance.

Mobile App Analytics

Your app tracks user behavior, screen time, and device type. If this behavioral data links back to a known user profile, it qualifies as personal data. If properly anonymized with no way to re-identify the user, it may fall outside the DPDP framework — but care must be taken to maintain strict anonymization.

Collecting Visiting Cards at Events

Scanning visiting cards to populate a CRM system involves collecting names, job titles, phone numbers, and email addresses — all of which are clearly personal data requiring lawful processing grounds under the DPDP Act.

Email Marketing Lists

Maintaining a database of names, emails, and city-level locations for targeted email marketing constitutes personal data processing. Even without Aadhaar or sensitive identifiers, this information must be classified and processed in line with DPDP obligations.

Personal data classification challenges are deeply embedded in everyday BFSI operations — often in ways that may not seem obvious at first glance.

A cautious, structured classification approach is therefore not just advisable — it is critical for building a DPDP-compliant data environment that can withstand audits, avoid penalties, and maintain customer trust.

A Practical Framework for Classification

To navigate the complexities of data classification under the DPDP Act, consider the following approach:

1. Overclassify When in Doubt

It's safer to treat borderline cases as personal data. Over-compliance poses minimal risk, whereas under-classifying personal data can lead to significant violations. If there is any ambiguity about whether a data point qualifies as personal data, BFSI firms should assume that it does. It is safer to collect valid consent or establish another legal ground for processing rather than risk non-compliance.

2. Categorize into Sensitive and Non-Sensitive PII

Not all personal data is equal. Divide it into:

Sensitive PII: Biometrics, financial records, health information, KYC identifiers.

- Apply strict access controls, encryption, and secure storage.

Non-Sensitive PII: Name, gender, occupation, phone number.

- Use moderate controls like masking and access logging.

3. Tag Data with Purpose

.avif)

Link each data field to a specific purpose—e.g., "email" collected for marketing communication. This helps justify processing under DPDP's lawful grounds and prevents purpose tracking. The classification of personal data should be determined based on its usage. If a dataset is being used to identify an individual, it must be treated as personal data under the DPDP Act. For example, a customer's CIBIL score alone may not directly identify them, but when combined with their PAN number, transaction history, or loan details, it becomes personally identifiable. BFSI firms must document and standardise purposes to ensure minimization of data collection.

The Bottom Line

Building clear classification systems today ensures smoother implementation of consent management, data minimization, breach notification, and individual rights fulfillment tomorrow.

When in doubt, classify conservatively, document your rationale, and train your teams to consider the purpose behind data collection and usage.

Because under the DPDP Act, it's not just about what you collect—it's about how and why you use it that matters.

Ready to simplify DPDP compliance for your organization?

Getting personal data classification right is just the first step. Managing consent, documenting purposes, and ensuring lawful data processing at scale requires a structured approach.

Leegality Consent Infrastructure is designed to help financial institutions implement DPDP compliance practically — without disrupting business operations.

Sign up using the form below to book a demo and see how Leegality can help you build a DPDP-compliant data foundation — effortlessly.

.avif)

.avif)